By Stephanie Ortiz

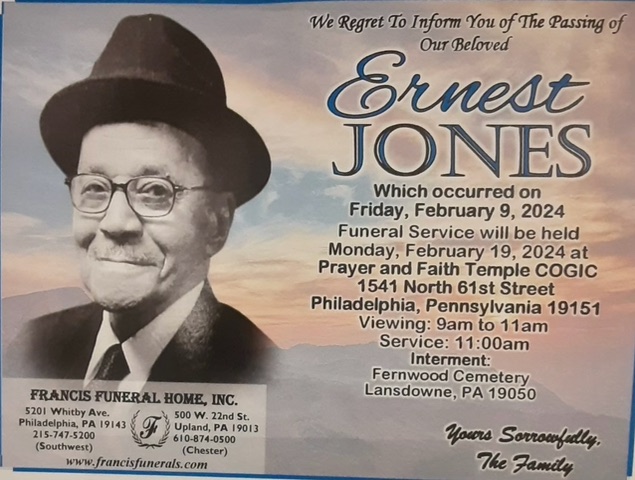

Pop Jones loved life for 107 years. Less than a year ago, he was quite the character when I met and interviewed him. But there comes a point when we all must go, and Pop Jones was ready for it. He told his son, 76ers legend Wali Jones, “It’s almost time. I’m tired,” five days before his death on February 9, 2024, during Black History Month.

Knowing how easy the transition was for Pop Jones didn’t make it easier for me.

It’s Black History Month. Shouldn’t 107 years be worth celebrating?

But I can’t lose Pop Jones to oversight or even to history.

Pop Jones had a personal story that can make a difference in our lives. He lived through the darkest times in history; if he did it then, we can do it now. It’s his legacy of love.

He passed this story to me, and I’m passing it to you like a torch. May it light our way.

***

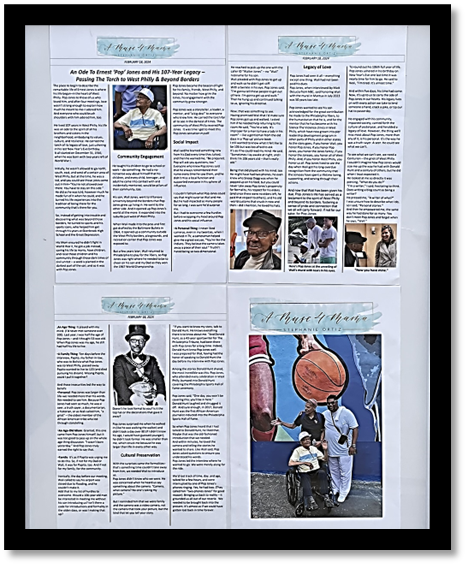

An Ode To Ernest ‘Pop’ Jones and His 107-Year Legacy – Passing The Torch to West Philly & Beyond Borders

The place to begin to describe the remarkable life of Ernest Jones is where his life began–in the heart of West Philly.

Pop Jones to those of us who loved him, and after four meetings, love wasn’t strong enough to explain how much he meant to me–I adored him. And everyone who could brush shoulders with him adored him, too.

He lived 107 years in West Philly; his life was an ode to the spirit of all his brothers and sisters in the neighborhood, embodying its values, culture, and resilience. He carried the torch of its legacy of love, just ushering in his last New Year’s Eve birthday.

It all started on December 31, 1916, when he was born with two years left of World War I.

Initially, he wasn’t allowed to go north, south, east, and west of a certain area of West Philly, but at the time, he was a kid, and you could see those jokes come out in him–“You’re not allowed over there. You have to stay on this side.”

He did as he was told, however much he made fun of it when he could, and he turned his life experiences into the tradition of being there for the community that’s there for you.

So, instead of getting into trouble and discovering what was beyond those borders, he turned to sports and his sports icons, who helped him get through his years at Overbrook High School and the Great Depression.

His Mom ensured he didn’t fight in World War II; he got a job instead, saving his life to marry, have children, and raise those children and his community through those dark times of civil unrest – a seed is planted in the darkest part of the soil, and so it was with Pop Jones.

Community Engagement

He taught his children to go to school or work – do something. He had a no-nonsense way about himself that his children, and every child, teenager, and adult he came into contact with and incidentally mentored, would be pillars of their community, too.

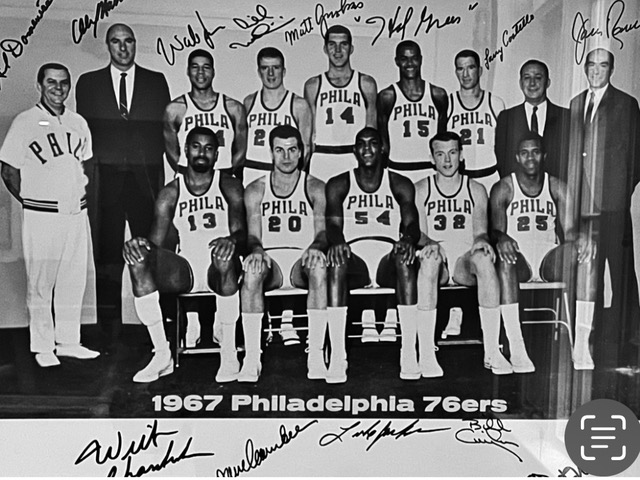

His son, Wali Jones, went to Villanova University beyond the borders that Pop Jones grew up living in. He went to the other side. And it opened up Pop Jones’s world all the more. It expanded into the suburbs just west of West Philly.

When Wali made it to the pros and first got drafted by the Baltimore Bullets in 1964, it opened up a community outside the West Philly borders, playgrounds, and recreation center that Pop Jones was exposed to.

But a few years later, Wali returned to Philadelphia to play for the 76ers, so Pop Jones was right where he needed to be to cheer on his son and my Dad as they won the 1967 World Championship.

Pop Jones became the beacon of light for his family, friends, West Philly, and beyond.

No matter how grim the times, his engagement with the community grew stronger. Pop Jones was a storyteller, a leader, a mentor, and “a big deal” to everyone who knew him.

He carried the torch for all to see in the darkest of times.

The community of West Philly revered Pop Jones.

It was time I got to meet this Pop Jones sensation myself.

Social Impact

Wali said he learned something new from his Dad every time they talked, and then he warned me, “Be prepared; Pop will ask you questions, too.” Everyone who knew Pop Jones said that he always remembered their name every time he saw them, and he didn’t miss a local function and supported everyone in his sphere of influence.

I couldn’t fathom what Pop Jones could say that might surprise Wali and me. But he had impacted so many people for so long, I was sure he’d surprise me.

But I had to overcome a few hurdles before wrapping my head around Pop Jones and his social influence.

- A Personal Thing: I never liked cameras; even in my twenties, when I worked in TV, a cameraman helped give me a great excuse, “You’re like the Indians. They believe the camera takes away a piece of their soul.” Truth? I hated being so two-dimensional.

- An Age Thing: It played with my mind. (I’d never met someone over 100). Last year, I was half the age of Pop Jones – and I thought 53 was old. When Pop Jones was my age, he still had half his life to live.

- A Family Thing: Ten days before the interview, Papito, my father-in-law, who was to Bolivia what Pop Jones was to West Philly, passed away. Papito wanted to live to 120 (and died pursuing his dream). Missing Papito, could I pull it together?

And those insecurities led the way to beliefs:

- Personal: Pop Jones was larger than life–we needed more than his words. We needed to see him. Because Pop Jones had seen so much, he was a seer, a truth sayer, a documentarian, a historian, or as Wali called him, “a griot” – the oldest member of the African American tribe who led through storytelling.

- An Age-Old Idiom: Granted, this one came from Pop Jones himself, but it was too good to pass up on the whole age thing discussion. “I wasn’t born yesterday.” And Pop Jones truly earned the right to say that.

- Family: It’s as if Papito was urging me to do this. So, if not for my Dad or Wali, it was for Papito, too. And if not for my family, for the community.

Ironically, the day before our meeting, Wali called to say his airport was closed due to flooding, and he couldn’t make it.

Add that to my list of hurdles to overcome. Would a 106-year-old man be interested in meeting me without his son introducing us? Isn’t there a code for introductions and formality in the olden days, or was I making that up?

Doesn’t he look formal to you? Is it the top hat or the decorations that gave it away?

Pop Jones surprised me when he walked in (like he was walking the walker) and didn’t look a day over 80 (if I didn’t know his age, I would have guessed younger); he didn’t look formal. He was smaller than me, which struck me because he was larger than life in every other way.

Cultural Preservation

With the surprises came the formalities–that’s something time couldn’t take away from him; we needed Wali to introduce us.

Pop Jones didn’t know who we were. He was concerned when he heard us say something about the camera. “Camera, what camera? No one’s taking my picture.”

But I reminded him that we were family and the camera was a video camera, not the camera that took your picture, but the kind that let you tell your story.

“If you want to know my story, talk to Donald Hunt. He knows everything there is to know about me.”

And Donald Hunt, as a 43-year sportswriter for The Philadelphia Tribune, had been there with Pop Jones for a long time. Indeed, Donald Hunt knew Pop Jones well.

I was prepared for that, having had the honor of speaking to Donald Hunt the day before my interview with Pop Jones.

Among the stories Donald Hunt shared, the most incredible was this: Pop Jones, who attended every celebration in West Philly, bumped into Donald Hunt covering the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame ceremony.

Pop Jones said, “One day, you won’t be covering this; you’ll be in here.”

Donald Hunt laughed and shrugged it off.

And sure enough, in 2017, Donald Hunt was the first African-American journalist inducted into the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame.

So when Pop Jones heard that I had talked to Donald Hunt, he liked that. Maybe that was the old-fashioned introduction that we needed.

And within minutes, he loved the camera and telling the stories he wanted to share. Like Wali said, Pop Jones asked questions to ensure you understood his words.

Pop Jones led the interview where he wanted to go. We were merely along for the ride.

We’d lost track of time, day, and age, talked for a few hours, and were interrupted by one of Pop Jones’s phones ringing. Yes, he had two. (They called him “two-phones Jones” for good reason). Bringing us back to reality – it grounded us all out of our reverie.

We needed to be brought back into the present. It’s almost as if we could have gotten lost back in time forever.

He reached to pick up the one with the caller ID “Walter Jones” – no “Wali” nickname for his son.

Wali pleaded with Pop Jones to get up and walk so he didn’t get stiff.

With a twinkle in his eye, Pop Jones said, “I’m gonna tell these people to get out of here. I’m gonna get up and walk.” Then he hung up and continued talking to us, ignoring his directive.

Now, that was something to see.

Having promised Wali that I’d make sure Pop Jones got up and walked, I asked him if he needed help returning to his room.

He said, “You’re a lady. It’s improper for a man to have a lady in his room” – like a gentleman from the old days in a ‘Pop-up’ picture book.

I still wanted to know what it felt like to be 106 but was too afraid to ask.

It’s as if he could read my mind. He said, “Sometimes I lay awake at night, and I think I’m 106 years old – that’s really old.”

Being that old played with his mind, too. He might have had two phones; he even knew who Snoop Dogg was when he popped up on his feed, but you could never take away Pop Jones’s propensity for formality, his respect for his elders (and since there were no elders left, he paid that respect to others), and his old world customs that snuck in now and then – did I mention, he loved his hats.

Legacy of Love

Pop Jones had seen it all – everything except one thing. Wali had not been paid his dues.

Pop Jones, when interviewed by Matt DeLucia from NBC, said honoring Wali with the mural in Mantua in July 2023 was 50 years too late.

Pop Jones wanted to see his son acknowledged for the great contribution he made to the Philadelphia 76ers, to the humanitarian that he is, and for the mentor that he has become with his Silence The Violence clinics in West Philly, which have now grown into pier leadership development program in other parts of Philly and in other states.

As the story goes, if you honor Wali, you honor Pop Jones; if you honor Pop Jones, you honor the Jones family; if you honor the Joneses, you honor all of West Philly. And, if you honor West Philly, you honor us all.

Pop Jones lived to see the day when Wali got his long-overdue recognition from the community that the Joneses have spent a lifetime loving, supporting, and serving through their actions.

And now that Wali has been given his due, Pop Jones’s life has served as a testament to the spirit of West Philly and beyond its borders, fostering a sense of pride and connection that we all will carry forward. If not for our sake, for Pop Jones.

Here’s Pop Jones at the unveiling of Wali’s mural with tears in his eyes.

To round out his 106th full year of life, Pop Jones ushered in his birthday on New Year’s Eve one last time.

It was nearly time for him to go. He said to Wali, “I’m tired. It’s almost time.”

And within five days, his time had come. Now, it’s up to us to carry the ode of Pop Jones in our hearts. His legacy lives on with every action we take to lend someone a hand, crack a joke, or tip our hat to passersby. He engaged with his community, impacted society, carried forth the culture of yesteryear, and heralded a legacy of love.

However, the thing we’ll miss most about Pop Jones, more than any of it, is his personal. It’s the way he was a truth-sayer. A seer. He could see what we can’t.

To see what we can’t see, we need a Centurian – the griot of West Philly.

I couldn’t imagine how Pop Jones would size me up the way he had with Donald Hunt and a century of others, but he did when I least expected it.

He looked at me so directly it was piercing, “What do you do?”

“I’m a writer,” I said, hesitating to think. Does writing a blog count as being a writer?

He pressed me, “A writer of what?”

I was unsure how to describe what I do, so I said, “Personal stories.”

And then he empowered me, the same way he had done for so many. You don’t meet Pop Jones and forget when he says, “Well.”

“Now you have mine.”

***

And, here’s one last story before I leave you.

Wali Jones received a surprise like no other – a mutual friend showed up at her doorstep with her 10-year-old granddaughter to hand-deliver a gift to commemorate Pop Jones.

Once Wali got over the shock of seeing them, he started talking about my article, which you just read. Our friend said, “That’s too bad I missed seeing it.” The 10-year-old winked at her Grandma, going along with it.

Meanwhile, Wali was holding this article – framed – in his hands.

For further reading, and to explore articles and videos on Pop Jones, please visit www.StephanieOrtiz.com